Over the weekend, Elizabeth Warren released a video denouncing stock buybacks in another of her trademark attacks on employers, attempting to sow resentment and divide Americans. Her usual style is to rely on rhetoric and academic theory that is difficult to parse and believable to those who’ve not studied a subject in depth. What’s striking about this attack, however, is that she illustrates the target of her wrath (corporations buying back stock) with a simple financial example, which falls apart with a cursory inspection and debunks her entire argument.

Warren is attempting to make the case that companies are manipulating their stock prices by buying back shares in their companies with excess cash. She seems to believe that this instantly increases the price of shares that are still traded.

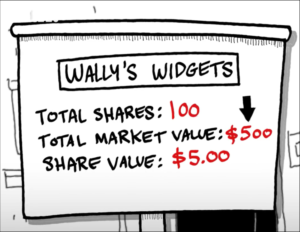

To illustrate this, she uses the simple example of a company named Wally’s Widgets. It has 100 shares valued at $5 each, giving the company a total market value of 100 shares x $5.00 = $500.

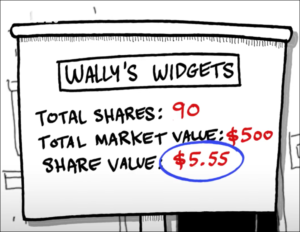

The evil CEO, in Warren’s mind, buys back 10 shares at a cost of $50, leaving a total of 90 shares on the market.

In Warren’s financial universe, the market value of Wally’s Widgets is unchanged at $500, which means that each share is now worth $5.55 because there are only 90 remaining. In her worldview, companies can at any time manipulate their stock price by buying outstanding shares, causing the remaining shares to increase in value.

This is where things fall apart. The total value of a company includes the value of its cash deposits. What does she think her greedy CEO is using to buy back the company’s stock?

When Wally spends $50 of his cash to buy back 10 shares, the total value is no longer $500, it’s $450. With only 90 shares now on the market, each remaining share is still worth only $5.00 (90 shares x $5.00 = the total market value of $450). In other words, the buyback Warren describes has no impact on the share price whatsoever.

That’s not to say that buying back stock (or sitting on large amounts of cash) can’t influence a share price. But absent any specific information or signals investors can glean from these actions or inactions, buybacks do not influence the value of shares.

Interestingly, initiating a stock buyback is often taken as a sign of good stewardship by investors. Insofar as a buyback signals that the company’s leadership has determined it’s already investing in the projects that will generate the best returns and that its excess cash could be better used outside the company, investors might bid up the value of a company’s stock.

On the other hand, a company hanging on to large stockpiles of cash can be a signal of poor stewardship if investors fear it might be used for low quality investments. They’re the sorts of corporations Senator Warren should be more concerned about. But given she has a penchant for supporting legislation that forces companies to spend their shareholders’ wealth complying with unnecessary and unproductive regulations, it was foreseeable that she’d attack an activity that is generally beneficial for investors.

Before becoming a senator, Elizabeth Warren was a law professor. Last month one of her brainchilds, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, was found to be unconstitutional. That she is now demonstrating she’s financially illiterate is perhaps unsurprising.

Isn’t the company just exchanging one asset for another of equal value? ($50 cash for $50 stock)? The valuation should stay the same in this case… assuming the company did not “retire” the shares. Same valuation, same number of shares overall, same share price.

If shares are retires the math get more involved, I think. You lose the value of the retired shares, and the share price will definitely change because the denominator changes.

Like you, I was pretty disappointed by the failed stock-buyback-will-definitely-increase-stock-price explanation, but I’m also disappointed you seem to be getting it wrong as well.

There’s real total market value (actual value of all assets the company holds minus its liabilities, aka “intrinsic value” or “book value”) and then there’s the stock-market market value. Since we’re talking about “total market value” as a multiplicative product of “share price” and “share number”, we’re talking about stock-market market value here. That is: it’s only determined by the number of shares and what people are willing to trade/buy/sell the stock price at…

It’s well known that the two are different and that there are smart cookies out there who intentionally arbitrage the difference (eg when the company is going bankrupt and needs to be liquidated) between real total market value and the stock -market market value, eg some of value-investor Graham’s students)

However, her accusations regarding CEOs who do buybacks due to skewed financial incentives may have merit:

https://www.fool.com/knowledge-center/does-a-stock-buyback-affect-the-price.aspx

The irony of this is that the buybacks may actually end up hurting stockholders who like to hold long-term if the buybacks are not done in a wise fashion.

Her accusations that the tax cuts failed in their intended effect: substantive increase in wages, also have merit, even if her analogy was utterly flawed. It comes at no surprise to anyone with an understanding of market economics of supply and demand that tax cuts would have done diddly-squat, especially directly, for wages. Only increased demand for workers (eg worker supply or increased production) would increase wages. Macroeconomic policy would suggest that instead of money spent on cutting taxes (because yes, decreasing gov’t revenue is same as spending it) the money could be spent on Keynesian inflationary spending…

Well. Wages for those without the means of reporting their income as capital gains instead.