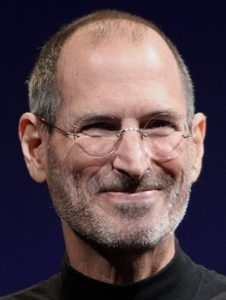

I recently read the biography Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson. It was an excellent portrait of one of the 20th century’s most creative entrepreneurs. Some of the stories – such as Apple’s complex history with Microsoft – were familiar, while others were new to me, including those of Pixar and NeXT. But I was also surprised to find some interesting insights into the need to reform America’s education system, both from stories of Steve Jobs’ formative years and in the opinions he expressed.

I recently read the biography Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson. It was an excellent portrait of one of the 20th century’s most creative entrepreneurs. Some of the stories – such as Apple’s complex history with Microsoft – were familiar, while others were new to me, including those of Pixar and NeXT. But I was also surprised to find some interesting insights into the need to reform America’s education system, both from stories of Steve Jobs’ formative years and in the opinions he expressed.

While the public elementary school Steve Jobs attended was fairly good, the middle school he was assigned to in Mountain View, CA, was awful. In the book, we learn that fights and shakedowns were a daily occurrence, kids regularly brought knives to school and Jobs was repeatedly bullied. As Isaacson explains it, his parents were barely making ends meet, but by the middle of seventh grade Jobs couldn’t take it any more and insisted they change his school. He quotes Jobs:

When they resisted, I told them I would just quit going to school if I had to go back to Crittenden. So they researched where the best schools were and scraped together every dime and bought a house for $21,000 in a nicer district.

It’s interesting to consider how different the world might be if his parents hadn’t been able to do this. Or to imagine what other kids he left behind at Crittenden might have become had they been able to escape as Jobs did. Would we have had Apple and Pixar? If some of his friends had an alternative, could they have transformed the world in other ways?

Roughly 50 years later, it’s remarkable how little has changed in most public school districts in the US. Like Steve Jobs’ parents, one of the key criteria for selecting the house my wife and I bought was ensuring the local public schools were some of the best in Seattle. For many, however, that’s not possible and they face the limited options of either sending their kids to schools like the one Jobs experienced or, if they have the means, paying for private school. Even if a public school is generally good, many parents often find it doesn’t cater to their child’s particular needs, forcing them to find a private alternative.

It’s little wonder that school choice initiatives have been finding bipartisan support in both red and blue states. Some of our most liberal friends, with whom we politely disagree on many issues, are enthusiastic supporters of charter schools. That’s consistent with national polls, which indicate 78% of parents would now support a charter school opening in their neighborhood. It’s no surprise that minorities and the poor, who generally live in urban areas with some of the worst public schools, are even more enthusiastic supporters, topping 80% in polls.

Unfortunately, there are usually far too few charter schools to provide parents with the alternatives they desire for their children. For example, in Washington State, there are only nine that are operational, with only a handful of them in Seattle. Current legislation restricts how many can open per year and caps total charters that can operate at 40. Not only does this mean there are still few options for most parents, but it also means the benefits of competition spurring public schools to improve is weak or non-existent.

Steve Jobs backed President Obama and even wanted to run the ad campaign for his second term, but, as Isaacson recounts, in one meeting with the president he discussed the US school system, saying it was:

…hopelessly antiquated and crippled by union work rules. Until the teachers’ union was broken, there was almost no hope for education reform. Teachers should be treated as professionals, he said, not as assembly-line workers. Principals should be able to hire and fire them based on how good they were. Schools should be staying open until at least 6 p.m. and be in session eleven months of the year.

Jobs also thought that “learning materials and assessments should be digital and interactive, tailored to each student and providing feedback in real time.”

Union dominated work rules and centralized school district bureaucracies hamper the sorts of innovations and experiments that Jobs endorsed. Charter schools, which have more operational flexibility, can and do adopt many of these approaches.

Better yet would be to implement the sort of independent school model that Sweden moved to in the 1990s. Schools there are funded based on the number of students they enroll and there are few restrictions on setting up schools. Enterprising parents and teachers have established schools when they’ve been dissatisfied with their local options. Contrary to some expectations, poorer Swedes have chosen independent schools at higher rates than affluent families. Other countries have moved to this sort of model as well, including Denmark, Chile, Ireland and the Netherlands.

Let’s hope the small wave of school choice that has been moving through the nation becomes a bigger wave. Too many kids are still stuck in Crittenden-like schools that, fortunately for America, Jobs was able to escape. Without more aggressive reforms, however, too many American children, particularly minorities and the poor, will continue to remain mired in mediocre education establishments and their potentials won’t be realized.

Cross posted at Sound Politics.

[…] lamentable public school system. Without going into detail about the core issues, which I’ve done elsewhere, the reasons behind this mediocrity are primarily an absence of choice or competition, and the […]